Performance measurement is a pillar of state quality improvement and oversight. It is often factored into plan payment, and it supports public reporting. In addition, starting in 2024, federal rules will require states to report performance on some measures, including some behavioral health measures, to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

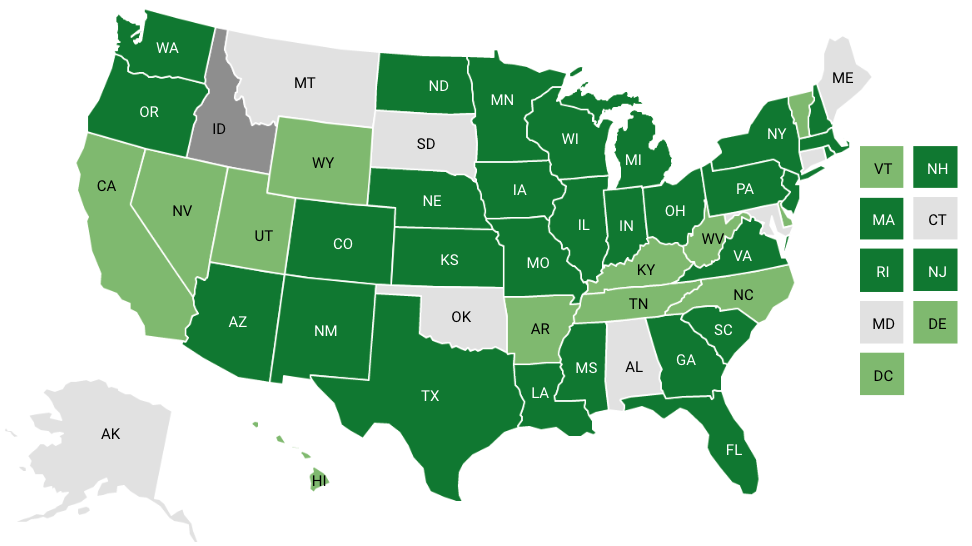

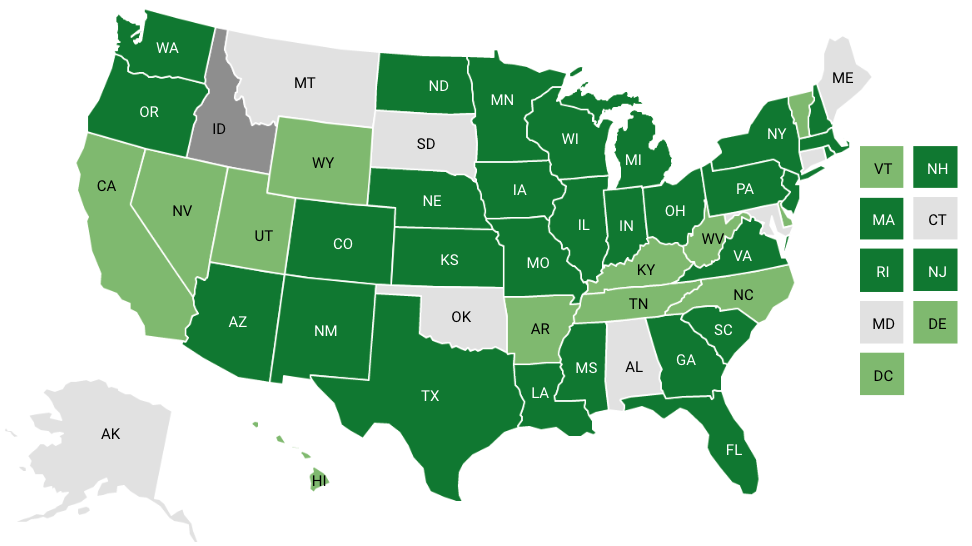

In late 2022, the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) conducted a scan of Medicaid managed care programs to identify which behavioral health measures states were collecting to measure behavioral health performance and if they were tied to payment approaches. We found that, in 2022, 42 states and Washington, DC, delivered behavioral health services to Medicaid beneficiaries through managed care plans.[1] All but one of these Medicaid agencies collected at least one measure of behavioral health performance. The complete set of data collected is available for download, and key findings about measure collection are presented below.

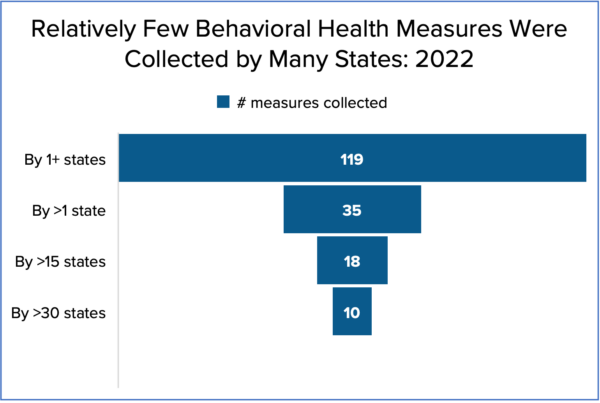

Together, the 42 Medicaid agencies that delivered behavioral health services through managed care plans collected a total of 119 different measures. However, the subset of measures used by more than one Medicaid agency was relatively small (see graph).

A similar pattern exists for the number of measures used in payment. States used a total of 50 behavioral health measures in plan payment, but only 15 of those were used by more than one state. Further, there is great consistency among the 10 most frequently collected measures and the 10 measures that are most frequently used in payment (Table 1). Notably, all of the measures in Table 1 are Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures or included in at least one of the CMS core measure sets.

Table 1: 10 Most Frequently Used Behavioral Health Measures: 2022| Measure (Alphabetical) | Rank Among 10 Most Frequently Collected | Rank Among 10 Most Frequently Used in Payment |

|---|---|---|

| Adherence to Antipsychotic Medications for Individuals with Schizophrenia (SAA) | 9 | 10 |

| Antidepressant Medication Management (AMM) | 2 | 5 |

| Diabetes Screening for People with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder Who Are Using Antipsychotic Medication (SSD) | 7 | 7 |

| Follow-up after Emergency Department Visit for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse or Dependence (FUA) — 7 Days, 30 Days | 4 | 4 |

| Follow-up after Emergency Department Visit for Mental Illness (FUM) — 7 Days, 30 Days | 3 | 2 |

| Follow-up after Hospitalization for Mental Illness (FUH) — 7 Days, 30 Days | 1 | 1 |

| Follow-up Care for Children Prescribed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Medication (ADD) | 5 | 6 |

| Initiation and Engagement of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse or Dependence Treatment (IET) | 6 | 3 |

| Metabolic Monitoring for Children and Adolescents on Antipsychotics (APM) | 8 | 8 |

| Screening for Depression and Follow-up Plan (CDF) (Combined with the HEDIS Measure Depression Screening and Follow-up for Adolescents and Adults (DSF-E)) | Not in Top 10 | 9 |

| Use of First-line Psychosocial Care for Children and Adolescents on Antipsychotics (APP) | 10 | Not in Top 10 |

Measures that become part of a national measure set go through a rigorous selection process. The details of the process differ among the bodies that establish each set, and different bodies involve different types and numbers of experts in their processes. However, there are several common elements in these processes, including that the measure has been validated, is evidence-based, is regularly updated — and a group of leaders in the field have determined that each measures an important aspect of care. In addition, CMS and the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) both produce national performance metrics that states can use as performance benchmarks. Finally, HEDIS measures bring the added benefit of an audit process so that both plans and state Medicaid staff can be certain that the reported measure accurately reflects performance. It is therefore not surprising that, when possible, states draw from these sets.

Most states do not simply adopt national measure sets in their entirety but rather implement a selection process that favors those measures but also considers other measures. The processes states use to select which measures they will use for oversight, payment, and public reporting varies widely. Oregon is among those states that conduct a formal measure selection process involving an expert committee with formal criteria for measure selection. Other states, such as Colorado, establish advisory committees that provide input on all aspects of a state’s quality improvement program, including measure selection. Many states, however, use a less formal process, but they still consider many of the same factors as the more formal processes.

States that deliver Medicaid services through managed care plans (including plans that deliver only behavioral health services) describe their process and considerations in a quality strategy that they are required to develop and maintain. In general, states consider their goals and objectives for the Medicaid managed care program, evidence that performance could be improved, the impact that improvement would have on health outcomes for the Medicaid population, and administrative burden. Pennsylvania, for example, reports in its quality strategy that measures are selected for inclusion in its pay-for-performance program based on past utilization that shows there is a need for improvement across the program and that improvement will benefit a “broad base” of plan enrollees. Most states also consider whether the performance standard they set for the measure is achievable.

Federal rules further reinforce the use of measures from the CMS core sets. Starting in 2024, states will be required to report both the behavioral health measures in the adult core set and all measures in the child core set to CMS.

Notably, the wide array of measures collected or tied to payment indicated new directions in delivery system improvement. Some states have included additional process measures to capture utilization along the continuum of care. Others have tied payment to behavioral health interventions with a robust evidence base. While much less commonly used, they provide examples of measures designed to shape care delivery through improved coordination and access to evidence-based care. For example, Pennsylvania incentivizes integrated-care approaches through tying payment to two integrated-care activities requiring coordination among primary care and behavioral health plans. New York incents “initiation of pharmacotherapy upon new episodes of opioid dependence,” and Georgia has tied payment to “the percentage of enrolled members who experience reduced behavioral health acute care stays AND increased functional status as determined according to agreed-upon validated instrument.”

States with managed care programs that serve populations unique to the Medicaid program, such as children in the foster care system, are particularly likely to use measures that are not part of a national measure set. Several states have added measures to these contracts that address goals or needed improvements specific to this population. For example, Ohio enrolls children and youth with complex behavioral health and multisystem needs into a specialized managed care program. The plan that serves these children and youth is required to report rates of out-of-home placement, out-of-state residential placements, and foster care placement disruptions due to behavioral health.

Other examples of measures that states are using to assess plan performance in delivering behavioral health services to specialized populations include the following.